Emphysematous Cystitis

AcknowledgementEmphysematous cystitis is an infection of the urinary bladder by gas-producing microorganisms. Whilst bladder wall gas is relatively easy to identify on abdominal plain film radiographic imaging, intraluminal gas within the urinary bladder can be more subtle and, importantly, can be confirmed with supplementary views. Radiographer identification of emphysematous cystitis on plain film abdominal imaging can expediate the performing of supplementary views and , in turn, facilitate speedy diagnosis and treatment.

I have quoted heavily from an article on the internet by S. J. Chong, K. B. Lim, Y. M. Tan, P. K. H. Chow, and S. K. H. Yip. This site provides an abundance of information on Emphysematous cystitis and includes comprehensive references. <a class="external" href="http://www.rcsed.ac.uk/journal/svol3_2/3020009.html" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">(http://www.rcsed.ac.uk/journal/svol3_2/3020009.html)</a>

<a name="DISCUSSION">History

</a>

The presence of gas within the bladder was first described in 1671 when a patient was said to have had passed “wind” through his urethra. This was initially termed “pneumouria” and, subsequently, was changed to “pneumaturia”. <a class="external" href="http://www.rcsed.ac.uk/journal/svol3_2/3020009.html" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">(S. J. Chong K. B. Lim Y. M. Tan* P. K. H. Chow S. K. H. Yip, Singapore General Hospital , Case Report, Atypical presentations of emphysematous cystitis)</a>

Aetiology

Primary pneumaturia (where there is intraluminal gas) was initially thought to be different from emphysematous cystitis (where there is intramural gas). However, in 1961, after reviewing 19 cases, Bailey suggested that the two conditions were part of the spectrum of the same disease.The cause of pneumaturia is divided into three categories:

1) due to instrumentation to the urinary tract;

2) due to a fistula between the bladder and the bowel, vagina or skin; and

3) due to infection.

The term emphysematous cystitis is used for the last category when there is pneumaturia due to an infection of the bladder, sometimes by Clostridium species but most commonly by the Enterobacter species. It is postulated that the microorganisms in the bladder cause fermentation of the urinary glucose. This in turn leads to the release of carbon dioxide bubbles which collect in the submucosa or lumen of the bladder. Besides glucose, it is possible that albumin may be fermented as well. Patients who are elderly or debilitated and with chronic retention of urine due to urinary outflow tract obstruction, structural or neurological abnormality of the bladder as well as those who are using indwelling urinary catheters are at higher risk of developing this form of infection. Holesh, in 1969, found that over 50% of patients were elderly and had concomitant long-standing diabetes mellitus. It also affects females more with a 2:1 preponderance. Although this condition occurs more commonly in the elderly and the immunocompromised, there are reports of infants having this condition as well. Of the organisms involved, E. coli and the Enterobacter species are the commonest. Other causes include Proteus mirabilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococci, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Nocardia, Clostridium perfringens and Candida albicans. It is worthwhile noting that a special culture technique is required to document Clostridium perfringens and it may be missed if the test is done only to detect aerobic organisms. <a class="external" href="http://www.rcsed.ac.uk/journal/svol3_2/3020009.html" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">(S. J. Chong K. B. Lim Y. M. Tan* P. K. H. Chow S. K. H. Yip, Singapore General Hospital , Case Report, Atypical presentations of emphysematous cystitis)</a>

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentations can be very varied and non-specific. They can include typical symptoms of urinary tract infection: urgency, frequency, nocturia and dysuria. In addition, many present with suprapubic pain and a large proportion of patients show macroscopic haematuria or pyuria, as in our third case. However, they may also present with non-specific symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, malaise, altered mental state and fever. There may be features of systemic sepsis and hypotension. Sometimes patients may present with an acute abdomen. The physical signs can vary from vague abdominal tenderness to overt pneumoperitoneum. One publication reported a presentation with subcutaneous emphysema and another of incidental findings from a CT scan done for other causes. Urine analysis may show pyuria, haematuria, bacteriuria, glucosuria or ketonuria. <a class="external" href="http://www.rcsed.ac.uk/journal/svol3_2/3020009.html" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">(S. J. Chong K. B. Lim Y. M. Tan* P. K. H. Chow S. K. H. Yip, Singapore General Hospital , Case Report, Atypical presentations of emphysematous cystitis)</a>

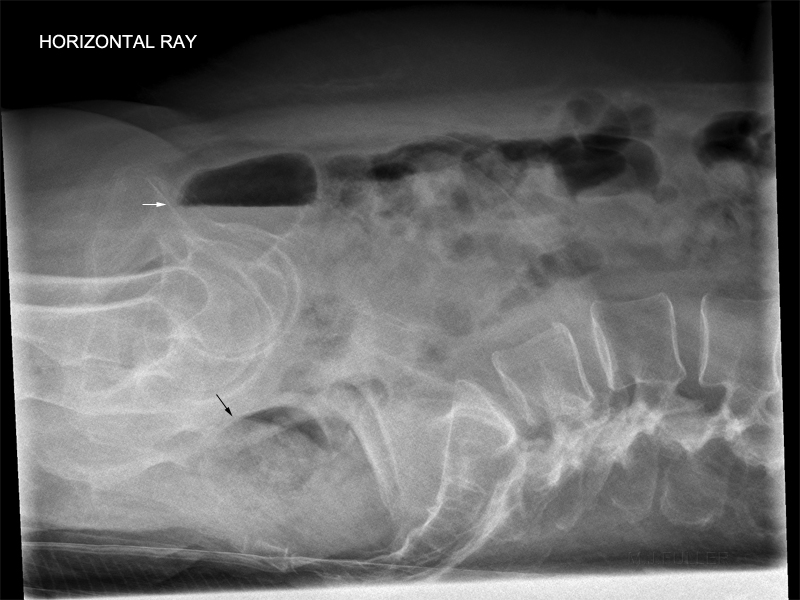

Plain Film Signs

Abdominal radiography may show a radiolucent line around the bladder wall or gas within the bladder giving a ‘beaded necklace’ or a ‘cobblestone’ appearance. There may be an air-fluid level seen within the bladder with patients in the erect position. Excretory urography may show gas within the bladder which may extend to the upper tracts. Computed tomography scans can clearly demonstrate gas within and around the bladder, as well as defining the extent of gas collection. Lund et al (1939) described what they saw at cystoscopy as a “silver sheen reflected from the convex surfaces of the extremely thin-walled vesicles studding the bladder mucosa, which were rupturing before our eyes and sending bubbles of air toward the dome of the bladder” Usually, there is evidence of marked cystitis with vesicles of various size and areas of haemorrhage. Purulent fluid, debris and clots can also be seen. Gentle manoeuvre of the cystoscope is important to avoid puncturing the thin-walled bladder. <a class="external" href="http://www.rcsed.ac.uk/journal/svol3_2/3020009.html" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">(S. J. Chong K. B. Lim Y. M. Tan* P. K. H. Chow S. K. H. Yip, Singapore General Hospital , Case Report, Atypical presentations of emphysematous cystitis)</a>

Treatment

The management of this condition involves prompt urinary drainage by means of a urinary catheter and the early use of appropriate broad-spectrum antibiotics. We recommend a third generation cephalosporin such as Ceftriaxone as first line therapy after the appropriate cultures had been taken. In our three examples, the urine cultures grew E. coli which was sensitive to Ceftriaxone. Other alternatives would be Ciprofloxacin and Gentamycin. In immunocompromised patients, consideration must be given to opportunistic organisms such as Candida albicans. Other co-morbidities such as diabetes mellitus should be treated concurrently. Issues such as the nutritional status, bedsores, ambulation should also be addressed. Surgery, such as debridement or cystectomy, is not often needed. However, if the disease progress to involve the ureters, kidneys or adrenal glands, extensive surgery may be required. Since carbon dioxide is readily absorbed in human tissue, eventual resolution usually occurs after elimination of the infecting microorganism by appropriate antibiotics. The urinary bladder has amazing regenerative potential and there had been several reports of patients who had sloughed the entire bladder mucosa only to regain completely normal bladder function. Thus, conservative management can be successful even in the presence of an acute abdomen and sepsis. The prognosis can be just as variable as the presentation ranging from a full recovery to death. Better outcome can be expected if the patient is not too ill at presentation and if the treatment is instituted early. As expected, the prognosis is worse if the condition involves the ureters, kidneys or the adrenal glands necessitating surgery. <a class="external" href="http://www.rcsed.ac.uk/journal/svol3_2/3020009.html" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">(S. J. Chong K. B. Lim Y. M. Tan* P. K. H. Chow S. K. H. Yip, Singapore General Hospital , Case Report, Atypical presentations of emphysematous cystitis)</a>

Case 1

Conclusion

... back to the Wikiradiography Home pageEmphysematous cystitis can be a difficult diagnosis on abdominal plain film in cases where there is no gas in the wall of the urinary bladder. Case 1 demonstrated that identification of suspected gas in the urinary bladder led to supplementary views which confirmed the presence of gas in the patient's urinary bladder. This reflects an advanced level of practice by the radiographer which facilitated speedy diagnosis and treatment of a condition which can vary in prognosis betweeen full recovery and death.

... back to the Applied Radiography home page